The Littlewood Treaty, The True English Text of the Treaty of Waitangi, Found

Chapter: Précis 1 2 3 4 5a, 5b, 5c, 5d, 5e 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 Lord Normanby's Brief Additional Resources

Chapter 10

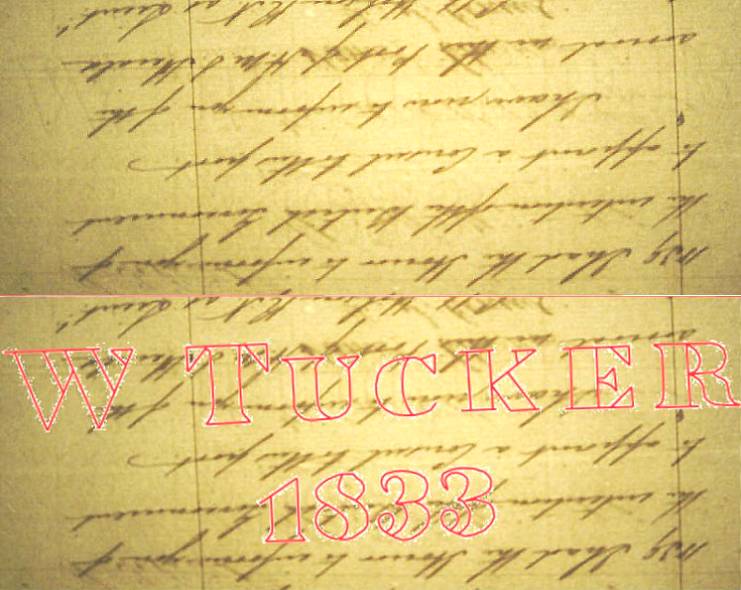

THE W TUCKER 1833 WATERMARK FOUND UPON THE LITTLEWOOD TREATY DOCUMENT

If the final English draft of the treaty had've been completed aboard H.M.S. Herald, then Hobson’s or Freeman’s on-board paper stocks would have been used. If Hobson had dipped into his personal stock, then, logically, the final draft would have been written on James Simmons 1838-watermarked paper. Had Freeman supplied the sheet from his secretarial stock, then it, seemingly, would have been Dewdney and Co 1838-watermarked paper.

Alternatively, if the final English drafting conference had've been held over at James Busby’s official Residence at Paihia-Waitangi, then the paper would have borne a J & J Town Turkey Mill 1838 watermark, consistent with Busby’s stock in use at that time.

Another brand that shows up in government despatches throughout 1840 is Harris and Tremlett 1838.

After the Littlewood Treaty document was examined by Dr. Claudia Orange in 1992 and the watermark identified as a W. Tucker 1833, Kathryn Patterson, Head Archivist at the National Archives, wrote the following to John Littlewood:

‘At National Archives there has been an item-by-item search through all surviving letters received and filed in 1840 and 1841 sequences for the watermark on the Littlewood document. No exact match has been found. Three items only paper watermarked “W Tucker” - one with the date 1836 and two with the date 1837 - and these provide no obvious handwriting similarity to the Littlewood document. An inspection of the Old Land Claim files relating to Clendon has not produced any relevant evidence’ (see Letter to John Littlewood from Kathryn Patterson, dated 12th of October 1992). Underling added.

On Monday the 17th of May 2004 I went to the University of Auckland’s microfilm section with research colleague, Brendon. We found the microfilm containing photo originals of U.S. Consular despatches sent by James Reddy Clendon to the U.S. Secretary of State. As we began reading the despatch letters, Brendon noticed the faint outline of a watermark on one of the pages and we strained our eyes to identify it, while adjusting the lighting of the microfilm reader. Brendon could, finally, make it out to be W. Tucker 1833. This was a very good and exciting find, which showed us that the final draft of the treaty was written, by Busby, on Clendon’s personal stock of paper. During the next few hours we were able to clearly identify several more pages amidst the Clendon despatches bearing this unique watermark.

Almost every letter despatch that James Reddy Clendon sent to the U.S. Secretary of State, John Forsyth between January 1840 and January 1841 positively contained some W. Tucker 1833-watermarked paper. To date, Clendon is the only individual in New Zealand known to have used this brand in his correspondence at the time. Some examples of the W Tucker 1833 watermark, appearing amidst his despatches, are found in:

• Fee endorsements’ letter, dated the 10th of January 1840 and covering “returns” from the 1st of July 1839 until the 31st of December 1839. This was received by the U.S. Secretary of State on the 18th of June 1840 and positively bears a W. Tucker 1833 watermark.

• Clendon’s 20th of February 1840 covering letter (despatch No. 6). It was received on the 15th of June 1840. Again the watermark is a W. Tucker 1833.

• The letter concerning Commodore Charles Wilkes’ safe arrival and departure, dated the 3rd of July by Clendon appears to be written on paper that bears the W. Tucker 1833-watermark.

• A letter concerning “returns” of American vessels that have entered this port for the half year ending 31st December 1840’ is on W. Tucker 1833 paper. This letter was written on the 11th of January 1841 (despatch No. 9).

It appears that no consideration has been given to watermarks, when tracing pedigrees of the draft notes of the treaty. By comparative analysis we can ascertain who owned a particular brand of paper and trace the movements of draft writers back to the locations where they kept their paper stocks.

Even on microfilm copies of Clendon’s Consular despatches, the W. Tucker 1833 watermark is clearly discernable. The top half of the above, two-part picture shows the faint outline of the W Tucker 1833 watermark. The bottom half indicates how it sits and appears on the same page. Clendon is the only individual in New Zealand known to be using this unique paper stock in February 1840, which points conclusively to him being the owner of the paper upon which the Littlewood Treaty was written. This watermark evidence further supports historian Ian Wards’ statement that Clendon was present when the English draft wording was worked out. Busby, quite obviously, penned it at Clendon’s premises, where Clendon kept his personal supply of paper. It seems unlikely that Clendon would have carried the paper to another venue. Either way, it was his paper stock.

Hobson’s drafting efforts were written upon James Simmons 1838 watermarked paper, which seems to have been his personal stock, in use when H.M.S Herald first arrived in the Bay of Islands.

Freeman’s drafting efforts were written upon Dewdney & Co 1838 paper and this brand seems to have been his N.S.W. government issued stock when acting in his capacity as Hobson’s secretary.

Busby held his personal stock of paper onshore at the official residence at Waitangi. Between the 2nd and 3rd of February 1840 he wrote two sets of treaty rough drafts on J & J Town Turkey Mill 1838 paper and submitted a clean copy of his efforts to Hobson at Kororareka on the evening of the 3rd.

Beyond the drafting stage.

Clendon’s presence at the final drafting stage of the English wording for the Treaty of Waitangi becomes very important in view of the events of the 20th of February and 5th of April 1840, when duplicate copies of Busby’s final draft (the Littlewood Treaty) were despatched to the government of the United States. The rapidly changing political climate of New Zealand would, over time, have major repercussions on the American whaling industry. The treaty had been signed amongst northern chiefs at Waitangi and Hokianga, as well as at Thames by March 1840. Britain had commenced a process of annexing New Zealand as a colony and territories within New Zealand were, systematically, being ceded in sovereignty to Queen Victoria. It was James Reddy Clendon’s duty as U.S. Consul to inform his superiors in Washington D.C. about the colonisation incentive underway, as well as the terms and conditions being entered into between the British Crown and the sovereign chiefs.

Document evidence shows that on the 4th of February 1840 James Reddy Clendon knew the final draft English wording of the treaty up to that point of development when he last saw it, undoubtedly at his own premises, where it had been written on his personal stock of paper. Whether subtle changes, additions or deletions had occurred to it after that time, he could not know, but it’s very apparent that on the 4th of February 1840 he transcribed a copy of the wording he’d helped to create, before it was taken away to Reverend Henry Williams for translation. As Consul to the United States of America, Clendon would need a copy for despatch, if Captain Hobson were ultimately successful in securing a treaty with the chiefs.

Clendon himself was a loyal Englishman and could be trusted by Hobson and Busby to hold any transcript or notes of the treaty wording he’d copied in absolute confidence until after a signing ceremony took place. Of Clendon’s outwardly apparent conflicts of interest or split loyalties, in being both a British subject and U.S. Consul at the same time, American Commodore Charles Wilkes was later to write these comments to the U.S. Secretary of State:

‘If the Govt. [U.S] should hold this in contemplation [securing an American treaty with the Maori chiefs] I should advise that a private agent of talent be sent out here to effect the object and that it be done with the assistance of our Consul here, [Clendon] who seems well disposed to forward the interests of our whalers, but being a British Subject he might be induced to prevent a very full arrangement and possibly might be the means of defeating the object if he was made the only agent to act. Already large offers have been made him to take office, which he has declined preferring his present situation to accepting anything connected to the Govt. here’ (see Papers of Charles Wilkes 1837-1847 pg. 166, U.S.S. Vincennes' Letter Book copy of despatch no. 64, Microfilm 1262, University of Auckland Library, pp 142-145 & 163-168).

James Reddy Clendon’s role in helping to secure a treaty between Queen Victoria and the native chiefs is largely glossed over in New Zealand historical circles. Clendon was a close confederate and friend of James Busby and was of constant assistance to the British Resident in establishing law and order in New Zealand from 1833 until 1840. Along with Reverend Henry Williams and George Clarke, Clendon was a member of Busby’s immediate support group and each of these gentlemen were contributors or cosignatories to both the 1835 Declaration of Independence, instigated by Busby, or the Treaty of Waitangi in 1840.

Of Mr. Clendon’s influence in convincing the chiefs to sign the Treaty of Waitangi document, Commodore Wilkes recorded in his journal:

‘About forty chiefs, principally minor ones - a very small representation of the proprietors of the soil - were induced to sign the treaty. The influence of Mr. Clendon arising from his position as the representative of the United States was amongst the most efficient means by which the assent of even this small party was obtained. The natives placed much confidence in him, believing him to be disinterested. He became a witness to the document, and informed me when speaking of the transaction that it was entirely through his influence that the treaty was signed’ (see The Treaty of Waitangi, by T.L. Buick, pg. 149 footnote).

The W. Tucker 1833 watermark found on Busby’s final draft attests to the participation of James Reddy Clendon at the final stage of drafting the Treaty of Waitangi.

Reverend Henry Williams and his 21-year old son, Edward, laboured

through the evening and night of the 4th into the morning of the 5th of

February to have the Maori translation completed in time for the meeting

before the chiefs. On the morning of the 5th of February 1840, Hobson landed

at 9 a.m. on the Paihia-Waitangi side of the bay in full dress uniform and

made his way to Busby’s Residence where the treaty assembly was to

take place. He met with Reverends’ Henry Williams and Richard Taylor,

as well as British Resident, James Busby, behind closed doors to discuss

the newly translated Maori treaty wording.

It’s very apparent that every effort was made to perfect Williams’

Maori translation right up until the last minute. Of the finished Maori

version created by Henry and Edward Williams during the previous night,

a historical account says:

‘Upon its completion the work was revised by Mr. Busby, who suggested the elimination of the word Huihuinga used by the translators, and the substitution of Whakaminenga more adequately to express the idea of the Maori Confederation of Chiefs’ (see The Treaty of Waitangi, by T.L. Buick, pg. 113).

The historical record tells us, therefore, that almost no alteration to the final translation was required other than the substitution of Busby’s preferred word to describe “The Confederation of United Chiefs”.

After the treaty meeting of the 5th of February 1840 got underway at midday, William Hobson read clauses from the English draft version and Reverend Williams repeated those clauses from the Maori translation version. During this segment of the meeting, no disputes arose from the crowd related to the accuracy of the translation being delivered and everybody seemed satisfied that Reverend Williams was representing Hobson’s English text correctly in the Maori language. Some disputes arose much later over other matters.

In December 2003, Dr. Phil Parkinson, in response to questions posed, expressed this opinion in his return letter, concerning the English text that Hobson read to the assembly:

‘Although nothing can be proven I think that what Hobson read was not the “Her most gracious Majesty . . .” text (which has a rather stiff and formal preamble) but rather the simpler and less formal Littlewood one “Her Majesty Victoria . . .” which in tone addresses the British listeners, rather than the Maori. Hence the Littlewood text says “ . . . seeing that many of her majesty’s subjects have already settled in the country and are constantly arriving, And that it is desirable for their protection as well as protection of the natives to establish a form of government among them.” Some people have made much of the absence of the words ‘lands and estates, forests and fisheries and other properties’ in the Littlewood document. However, the expressions it uses “The Queen of England confirms and guarantees to the chiefs and tribes and to all the people of New Zealand the possession of their lands, dwellings and all their property . . .” is just as effective, only less wordy than that in the official English text; the point is that all property is confirmed, of whatever kind, so it is unnecessary to go into details about forests, fisheries, mineral rights or anything else’

Doctor Parkinson further stated:

‘Dr Orange, in a document of 5 October 1992, considered that Dr Loveridge was “probably correct” in deducing that the Littlewood document was “a translation of the Maori treaty” but what Loveridge said was that the “translation from the native document” and “the Maori version on which it was based” both bore the date of 6 February (rather than 4 February). But this is not really satisfactory. The Busby / Littlewood document of 4 February is not a translation of the Maori text of the treaty because that translation was written on 5 February, by Henry Williams.’ (see: Letter response from Dr. Phil Parkinson to Martin Doutré, 25507 Doutre, AT 13/19/4, 24th of December 2003).

So, we see that, in Dr. Phil Parkinson’s view of December 2003, it was the Littlewood Treaty English version that was read by Hobson to the assembled crowd at Waitangi. According to Dr. Parkinson’s belief at the time, the Littlewood Treaty existed as a fully-fledged document and text prior to the Treaty assembly on the 5th of February 1840. His comments also show that Dr. Parkinson believed the 4th of February 1840 date, written on the document, to be correct and not a latter era mistake by someone writing the wrong date on a back-translation created weeks, months or years later. If, as he believed in December 2003, the Littlewood Treaty was read to the crowd, then it must have been the last known English draft of the Treaty of Waitangi and the mother document to the Maori Tiriti O Waitangi.

In a National Business Review Article of March 4th 2005, Dr. Parkinson expresses an altogether different point of view to the one he held a little over a year before. The article reads:

‘Phil Parkinson, a former national archives historian

who originally identified the Littlewood Treaty document as the handwritten

work of James Busby, the senior British resident at Waitangi, is also about

to publish his own take on the affair “in order to quieten this debate

down or at least answer the questions.”

Dr. Parkinson, whose book is approved by historian Claudia Orange, will

debunk the Littlewood treaty as a curious but meaningless document, which,

in Parkinson’s considered view, was one of several versions written

nearly two weeks after the February 6, 1840 treaty signing.

Dr. Parkinson said the Littlewood document, while it was dated February

4, was not a draft of the treaty as Mr. Doutré and his supporters

claimed it was.

The Littlewood document was a back-translation from a text in Maori into

English in Mr. Busby’s handwriting, but printed between February 17

and 20 and mis-dated Mr. Parkinson said’ (see National Business

Review, pg. 13, March 4, 2005).

Dr. Parkinson’s new position is in stark contrast to that of historian Graham Langton, who is also quoted in the National Business Review article:

‘Archivist and historian Graham Langton said the Littlewood

Treaty had “no status whatsoever” but unlike Dr. Parkinson’s

view, said it was “very likely” it was documentation from before

the signing of the treaty on February 6.

Mr. Langton said “it was probably a draft version and it was possible

it was the final draft but added: So what?”

It was not signed. The real treaty, finalised on February 4, was the version

in Maori signed on February 6, Mr. Langton said.

He said the problem with the Littlewood document - which he said was possibly

a genuine draft from 1840 - was it could not be traced from the present

day to its actual creation.

“The issue is what does it matter anyway? The Treaty is the one that

was signed. The Maori version is the real treaty. This is a nice curiosity

but still does not make a treaty’

Unlike Dr. Phil Parkinson, historian and archivist Graham

Langton is prepared to concede that the Littlewood Treaty is ‘a

draft’, as opposed to a back-translation of the Treaty of Waitangi.

In so doing he must also concede that the date written at the bottom of

the document, the 4th of February 1840, is not a mistake, but was deliberately

put there by its author, James Busby. If that date is correct, then it naturally

follows that the Littlewood Treaty is the final draft of the Treaty of Waitangi

and the official English wording. The Littlewood Treaty is the only complete

draft known to exist, with a Preamble, three Articles and an Affirmation

section. If it is a draft, then it is the final draft, as it is the natural,

more developed advance on Busby’s rough notes of the 3rd of February.

No further drafting took place beyond the 4th of February, as the task of

translating commenced in the late afternoon of that day.

This is what my colleagues and I have been trying to convey to our establishment

historians. The wording of the Littlewood Treaty constitutes the final English

wording of the Treaty of Waitangi and Te Tiriti O Waitangi was derived from

these exact words.

The Littlewood Treaty wording was translated into the Maori tongue, beginning at 4 p.m. on the 4th of February 1840. In Article II of the final draft it states that the rights enshrined by treaty are for all the people of New Zealand - altogether, with no special rights for any one group over any other. This is exactly what the Maori Tiriti O Waitangi says in Article II. All underlining of quotes added.

So, in answer to Mr. Langton’s ‘so what?’… let me ask him a question…If, as you almost acknowledge, the Littlewood Treaty is the final English draft of the treaty, then for what insane reason are we using an illegitimate, non-treaty, English text, based upon a defective, superseded draft from the day before, in all of our legislation? Furthermore, why has that defective 3rd of February English wording eclipsed, supplanted and replaced the true treaty wording, as found in Te Tiriti O Waitangi?

In answer to Mr. Langton’s comment that ‘It was not signed’…Hobson’s government intended that no English version ever be signed by the Maori chiefs. Proffering an English version for the chiefs to sign was tantamount to asking Hobson, in return, to sign a contract in Cantonese. The English versions were simply rough drafts, leading up to a final draft. After Te Tiriti O Waitangi became a reality, James Stuart Freeman produced a variety of “Royal Style” English versions, solely for despatch overseas. One of these, without government sanction, mistakenly found its way to Port Waikato, where some overflow signatures came onto it after Reverend Maunsell had read the correct Maori text to the assembled chiefs. The chiefs coming forward commenced signing the printed Maori document, in the meagre two inches of available space at the bottom, but quickly ran out of room. The overflow signatures of the other 32 chiefs ended up on the defective English document, which had not been presented on the day, nor sent to the proceedings by the government. This was the only such, otherwise innocent, procedural mistake made in the entire treaty presentation incentive, spanning many months and involving 540 signatory chiefs in many scattered districts.

As an archivist and historian Mr. Langton must know that we can trace the whereabouts of the Littlewood treaty ‘from the present day to its actual creation’. Working from the day of its creation, it went from Busby to Hobson to Williams to Hobson to Clendon (via Shortland) to Henry Littlewood (solicitor) to Littlewood’s descendants to Beryl Needham (Henry Littlewood’s great-granddaughter) to the Auckland War Memorial Museum to John Littlewood (Henry Littlewood’s great-grandson) to the National Archives. The more recent dates when it changed hands are known exactly or the more remote dates are easy to calculate to within a small interval in time. We have a fair idea how long it remained in the possession of any one individual from its inception through to the present day.

The fact that the Littlewood Treaty existed as a treaty draft,

on the 4th of February 1840, before the Maori version was even created,

is also supported by a view expressed by Dr. Paul Moon, who wrote the following

to historian, Ross Baker:

‘I agree that the Littlewood document is dated 4 February 1840,

and that there was almost certainly no subsequent drafting of the Treaty’s

English text’ (See excerpt from Dr. Paul Moon’s letter to treaty

researcher, Ross Baker, 30/08/2004 and posted onto the O.N.Z.F. website).

In Dr. Paul Moon’s book released in November 2004, one

can only interpret that there is acknowledgement of the Littlewood Treaty

being the lost final draft of the Treaty of Waitangi. Moon & Biggs write,

in muted, half-hidden tones:

‘On 30th March, US Commodore Charles Wilkes, Antarctic explorer,

arrived in the Vincennes to join his other ships Porpoise and Flying Fish.

Damaged after their bruising exploration of the icy land, they reprovisioned

and repaired their ships till late April. As he left Clendon gave him a

further despatch containing a hand-written copy of the Treaty in English

copied from Busby’s copy of the final draft. It is believed that

Clendon then retained Busby’s copy of the Treaty’ (see The

Treaty and Its Times, by Paul Moon & Peter Biggs, chpt. 9, pg. 213).

Moon and Biggs at least acknowledge that the Littlewood Treaty text is the final draft wording, although their description of ‘a hand-written copy of the Treaty in English copied from Busby’s copy of the final draft’ is a bit confusing. Either Wilkes or his secretary copied directly from Busby’s final draft for despatch number 64 to the U.S. Secretary of State. Thereafter, yet another copy was recorded in the U.S.S. Vincennes’ letter book, which is now in the collection of the Kansas Historical Society of Topeka, Kansas. In all, four copies of the final draft are known to exist, although the one sent in Wilkes’ despatch 64 to Washington D.C. has not, as yet, been viewed by this researcher.

In the end it all gets a bit academic and it seems like there’s a lot of unnecessary nit-picking nonsense being bantered about amongst our acknowledged experts. The bottom line for ordinary New Zealanders is that we want our true treaty wording back. Up until about 1975 we thought we knew, quite definitively, what our treaty meant. As a consequence, all of us coexisted, quite happily, in an egalitarian society, under a mantel of protections guaranteed to “all the people of New Zealand” by the Treaty of Waitangi / Tiriti O Waitangi compact.