The Littlewood Treaty, The True English Text of the Treaty of Waitangi, Found

Chapter: Précis 1 2 3 4 5a, 5b, 5c, 5d, 5e 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 Lord Normanby's Brief Additional Resources

Chapter 13

HOBSON, BUSBY & WILLIAMS DID THEIR JOBS VERY ADEQUATELY

In July 1861, Busby published Hobson’s letter of thanks to him for his endeavours in preparing a treaty. Busby writes:

‘In writing to me afterwards he expressed himself in the following words:- “I beg further to add that through your disinterested and unbiased advice, and to your personal exertions, I may chiefly ascribe the ready adherence of the chiefs and other natives to the Treaty of Waitangi, and I feel it but due to you to state that, without your aid in furthering the objects of the Commission with which I was charged by H.M. Government, I should have experienced much difficulty in reconciling the minds of the Natives, as well as the Europeans who have located themselves in these islands, to the changes I contemplated carrying into effect.” (See Appendix to Journals July 1861, E. No. 2 page 67).

Certain New Zealand historians have been anything but kind in their estimation of the abilities of Lieutenant-Governor William Hobson, British Resident, James Busby and C.M.S. Senior Missionary, Reverend Henry Williams. Some seem almost unable to mention the names of these three individuals without succumbing to the temptation of attaching derogatory labels and taking sarcastic swipes at these important founding fathers.

.

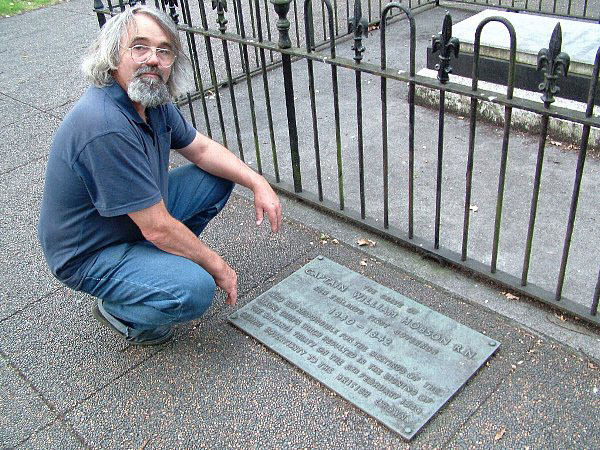

The author by the grave of Governor William Hobson at Grafton Bridge Cemetery, Symonds Street, Auckland. In the past thirty years Hobson’s character has been much maligned by certain historians. For Hobson, we’re often reminded of his ‘modest’ abilities or ‘humble’ intellect, etc.

Governor Hobson, Resident Busby and Reverend Williams are sometimes made

to look like the 3-stooges…Moe, Larry and Curly. Hobson, especially,

is portrayed as an inept, bungling executive who didn’t properly check

the legal implications of what Busby wrote into the English Treaty of Waitangi

draft. We’re led to believe that, because of Hobson’s supposed

inattention to detail, he didn’t achieve his objective of having sovereignty

ceded to Queen Victoria.

Photo: courtesy of “Harry” Harrison.

Busby, supposedly, forgot to mention any rights for the settlers when he wrote Article II of the treaty, despite the fact that Hobson had travelled halfway around the world with a commission from Queen Victoria, specifically to secure those rights.

Reverend Henry Williams has been variously portrayed as a very poor translator who really muffed the translation from the English to the Maori or, as one leading grievance-industry historian now mischievously suggests, deliberately conspired to mistranslate the treaty in order to stop the British from achieving their objective.

Hobson was a man of integrity, empathy and very reasonable ability, who had come from a distinguished career as a Captain in the British Royal Navy. His exploits in dealing with pirates in the Caribbean and displays of uncompromising courage in the face of death when captured became legendary.

Captain William Hobson first arrived in New Zealand aboard H.M.S Rattlesnake on the 27th of May 1837, to help quell the tribal warfare that had broken out between Titore and Pomaré II, in which the settlers were threatened. Marianne Williams, the wife of Reverend Henry Williams, described Hobson as:

‘a thin, pleasing man, said to be the original of ‘Tom Cringle’ [a popular, daring but fictional maritime hero, who fought pirates in the Caribbean region] of ‘The Log’ [a book released in 1834 by Michael Scott] (see Te Wiremu, by Lawrence M. Rogers, pg. 135).

‘When Hobson left St. Helena at last he had been at sea on continuous duty for thirteen years and by then he had been made a first lieutenant. In 1821, Hobson commanded the sloop Whim, assigned the task of attacking pirates in the West Indies and it was there that he met the novelist Captain Marryat, furnishing that writer with material for many of his sea stories. Michael Scott, another novelist, made Hobson the hero of a somewhat famous yarn, “Tom Cringle’s Log” which was said to be, in reality, an account of Hobson’s West Indian adventures. He and his crew were captured by pirates in 1821, but released after a week of ill treatment. He was captured again in July 1823 while commanding a small flotilla attacking pirate strongholds. He made a daring escape and continued with his operations; the pirate chief who had captured him in 1821 was routed and driven to his death. During his West Indian service Hobson was afflicted by yellow fever three times, and suffered recurrent headaches for the rest of his life’ (Extracted, in part, from a series of articles in the Waterford News Aug 12/ Sept 16, 1938; from The Oxford Illustrated History of New Zealand, and from Hobson, William 1792 - 1842, by K.A. Simpson, also Dictionary of New Zealand Biography).

Hobson’s major impediment, upon arrival in New Zealand,

was that he was already quite ill, as he’d never fully recovered from

his earlier bouts with yellow fever. He was very susceptible to stress and

Governor George Gipps’ choice of Captain Nias to cooperate with Hobson

and his staff, in all of their transportation requirements in and around

New Zealand, appears to have been an almost disastrous decision. Nias, simply,

didn’t want to be there, as he had orders to proceed to a conflict

in China and saw Hobson’s commission as secondary to his own very important

assignment from the admiralty. Perhaps Nias also resented Hobson’s

pseudo folk hero status, as the inspiration behind the character, “Tom

Cringle” of popular pulp fiction fame.

Hobson’s paralytic stroke, which put the whole treaty signing incentive

and hopes for a stable colonial government into severe jeopardy only 1-month

after his arrival in New Zealand, appears to have been fully attributable

to, what Hobson would have perceived as, the obstreperous attitude of Nias.

Despite this unfortunate clash of personalities, which was stressful, nigh-unto-death for Hobson, he still managed to organise a programme of writing, then presenting, a clear and concise treaty wording. Had the original texts, in both English and Maori, remained continuously with us, they were more than adequate to provide a solid foundation upon which a successful bicultural and egalitarian society could be built.

During most of his first month in New Zealand, Hobson felt like death warmed over. The constant fights with Nias, apart from sapping Hobson’s energy, also seemed to have an effect on his self-confidence. At the same time, being outside his own patch, or a stranger in a strange land, and fully reliant on the missionaries to organise itineraries of where to go and who to see, forced Hobson to be constantly seeking advice from others. He was trying to organise order out of chaos in an undeveloped country. His situation of being hopelessly at the mercy of go-betweens to arrange access to the isolated chiefs he needed to talk to, as well as his ever-present uncertainty related to what could be accomplished next, was the source of some criticism towards Hobson. Felton Mathew writes concerning events of February 27th 1840.

'Our leader’s movements - I shall not call them plans, - for he has none - are very feeble and vacillating - And like a man who is less to his station, he seeks to strengthen his opinion by the judgement of others - and is perpetually seeking what he calls information, from the missionaries & others, who are the very parties interested in misleading him: And yet he is obstinate as a pig too, and thinks that no one knows anything but himself'.

And again for March 7th, a week after Hobson had suffered his stroke:

'We have had such an explosion this morning between the two Captains, who are both obstinate, wrongheaded fellows, & as fit to act together as fire and toe - The quarrel has been very violent, and the consequence has been the framing of a set of minutes of the conversation that took place, for the purpose of transmitting them to Govn George Gipps - Where this matter may end, tis impossible to foresee - it may occasion our recall to Sydney - perhaps even to England - the immediate effect in that the Govn says we must all leave the ship this eveng - Meantime this is the way in which the public service is conducted, by two men, neither of whom are at all qualified for the duty to which they have been appointed - Nothing but broils have occurred - and the whole affair has been one scene of folly and imbecility from beginning to end - Captn Hobson will kill himself in six months, if he continues here, as it appears he has determined to do - You will see [from an earlier letter] how I admired the manly way in which, when he was first attacked [by stroke induced paralysis], he formed at once the resolution of resigning the Govn and returning to Sydney. No sooner, however, does he become a little better, than he alters his intention, still clinging to the loaves and fishes/- this perhaps natural; but alas, poor human nature! - Captn Nias has certainly shewn great want of feeling and much indelicacy in wishing to hurry Hobson out of the ship:- but the latter again is a most disagreeable person to have anything to do with, and has been in many things much to blame - I do not think that any officer will serve with him for twelve months - It is very doubtful if I shall do so, for so long a period.'

Generally, Felton Mathew was a little kinder and more forgiving than this, but he had just returned from a horrendous two-week voyage, often interspersed by terrible, buffeting storms. He’d seen his exploratory expedition with W.C. Symonds, to the southward, cancelled because of Hobson’s stroke and, like James Stuart Freeman, was in painful longing for the company of his wife. He was, by this point in time, at his wits end and had a frayed, short temper. Mathew wrote on the 2nd of March 1840:

‘Poor Freeman too is very anxious about his wife, and looks and is very unwell. - In fact being cooped up in this infernal ship is playing the very devil with us - and that is plain English or I know not what is’.

Hobson, upon first arriving in New Zealand, had the foresight to rely upon a few seasoned and experienced delegates to aid him in the treaty writing incentive. Busby, graciously, jumped into the breach at very short notice, realising that his replacement Consul was experiencing inspiration-sapping illness and insurmountable difficulties.

Within a day or two of concentrated effort, Busby took some very raw concepts and fashioned them into the basis of a coherent and rational treaty, which largely complied with the written requirements of the British Colonial Office. His efforts were then laid before other informed and humane peers, who, like himself, had a record of caring deeply about the rights of the Maori people. The much sought-after approbation of Hobson and Busby’s ecclesiastical or secular mentors could not be entertained or won unless the final treaty text was seen to be wholly advantageous to the protection, betterment, safety and future prosperity of the Maori people, found in their congregations or counted amongst their close, personal friends*.

*Footnote: Reverend Henry Williams desired very strongly that something be done to bring law, order and protection to the Maori people and law-abiding settlers alike:

‘In 1837 he had written to his brother-in-law, enclosing a copy of a petition from the several British subjects in the Bay of Islands, which had been forwarded to the King. This petition asked for the intervention of the British Government to control the unruly European element. In his letter Williams wrote:

‘It is high time that something be done to check the progress of iniquity committed by a lawless band daringly advancing in wickedness and outrage, under the assurance that ‘there is no law in New Zealand’. Without some immediate interposition on the part of the Government for the protection, our position will become very desperate, as we may expect to be surrounded ere long by a swarm of rogues and vagabonds, who indeed carry all before them, both as respects the respectable European and also the natives.’

In 1838, writing to the Church Missionary Society on the proposals of the New Zealand Association, he said: ‘The English Government should take charge of the country, as the guardians of New Zealand…” (See: Te Wiremu, by Lawrence M. Rogers, pg. 163).

Busby had worked hard as British Resident for seven years by the time Hobson arrived. In the pre-treaty years he strongly supported ‘education for Maoris, the founding of a Maori newspaper and, at a time when Maori were selling much of their land, the setting aside of ample reservations.

He proposed also a council of settlers, missionaries and Maoris who would advise the Resident…Busby had his own salary constantly drained, for during his seven years as Resident, a quarter of it went on presents to chiefs. It was no wonder he was bankrupt at the end of his appointment’ (see New Zealand’s Heritage, Vol. 11, pp 289-290).

During this period he tried to raise the international profile and recognition of the sovereign chiefs of New Zealand, by helping to form the Confederation of United Chiefs into a unified body and write their Declaration of Independence for them. This 1835 text by Busby, sent overseas to be published abroad, was translated into Maori by Reverend Henry Williams, with the signatures of the northern chiefs witnessed by Henry Williams, James Reddy Clendon and George Clarke. This group was Busby’s support team and all contributed to the Treaty of Waitangi.

Regarding Busby’s latter years:

‘The final paradox in Busby’s character is that, although he was New Zealand’s first public servant, he was also its first political protester. In words of force and dignity he said, “I hold to be the highest duty to which a citizen can be called to oppose… the unlawful and unjust acts of persons in power”…Busby edited and financed his own paper, The Aucklander. This paper survived only two years because, again on principle, Busby would not insert paying advertisements’ (see New Zealand’s Heritage, vol. 11 pg. 291).

As for Reverend Henry Williams, Historian, Dr. Claudia Orange wrote somewhat disparagingly:

‘Hobson then asked Henry Williams, a senior CMS missionary, to translate the treaty into Maori, which he did with the help of his twenty-one-year-old son Edward on the evening of 4 February. Although they were comfortable using the Maori language, they were not experienced translators; indeed, there were few people with such skills at the time. Henry’s brother William might have been a better choice, had he been there.’ (See An Illustrated History Of The Treaty Of Waitangi, by Claudia Orange, 2004).

Red-herring alert: This is a very unfair assessment, embraced by some present-day, grievance-industry aligned historians, that Henry Williams was not equal to the task and that Reverend William Williams or Reverend Robert Maunsell should have been chosen as the treaty translators in Henry’s stead.

Certain of these social-historians portray this 17-year-long serving veteran, at the head of the C.M.S organisation, as incompetent, or infer that his assistant son, Edward Marsh Williams, was an inexperienced boy trying to do a man’s job. There is nothing in the historical record to support this dismal estimation of the linguistic skills shared by either Henry or Edward Williams.

Henry Williams had arrived in New Zealand in 1823 when Edward was only about 4-years of age. Young Edward had been raised in a Nga-Puhi iwi environment and was equally conversant in Maori or English. He was able to composed very eloquent reports in either language and is referred to in early colonial history writings as a "scholar par excellence" in the Nga-Puhi dialect.

In fact all the combined clergy of the day saw the importance of learning the Maori language fluently. They were focused on the necessity of producing accurate grammars or dictionaries as aids to the constant, on-going translation of religious and other literature into the Maori tongue. The first important Maori language-aid book produced was Grammar And Vocabulary, by Kendall & Lee, 1820. Chief Hongi Hika was a major contributor to this publication.

‘The printing press played a significant part in the

rapid progress of the Mission. At the schools the Maoris, old and young,

were taught to read, and they in their turn were ready to teach others.

The result was that as time advanced a large number of Maoris eagerly awaited

satisfaction of their new ability. The supply never equalled the demand.

Before books could be printed, translations had to be made and this took

time.

The first book printed in Maori was Kendall’s A Korao No New Zealand

or the New Zealander’s First Book, Being an attempt to compose some

Lessons for the Instructions of the Natives.

By 1824 James Shepherd had compiled a vocabulary, translated some hymns, and was at work translating the Gospels. After the arrival of Henry and William Williams, [1823] all the members of the Mission met regularly for the study of the language and for translation. Later a Translation Committee was set up and carried on this work for many years. In 1827 Shepherd had translated some selected passages, with some hymns, and this was published in Sydney. In 1830 five hundred and fifty copies of a slightly larger selection of Scripture passages were printed and these were eagerly purchased.

Yate, who had gone to Sydney, to see this volume through the press, brought back a printing press, but it proved unsatisfactory. In 1833 the whole of the Liturgy, two gospels, the Acts of the Apostles and three Pauline epistles, with some hymns, were printed in Sydney, and the 3,300 volumes printed found ready Maori owners in New Zealand.

The arrival of Colenso and Wade with the new printing press in December 1834 was welcomed by both missionaries and Maoris. The printer went to work immediately and in February 1835 the printing of 2,000 copies of William Williams’s translation of the Epistle to the Ephesians and Philippians was completed. When Colenso next printed Luke’s gospel, he could not bind copies fast enough to meet the demand. By 1836 William Williams had completed a translation of the New Testament and Prayer Book, of which Colenso completed the printing in December 1837. An edition of 3,000 copies of the Prayer Book was commenced, but demand was so great that 33,000 abridged copies were printed before the complete Liturgy was published in 1841.

When Maunsell arrived in 1835, he began to share with William Williams the task of translating the whole Bible’. (See: Te Wiremu, The Biography of Henry Williams, by Lawrence M. Rogers, pp. 159-160).

By the time of the treaty in 1840, the entire New Testament of the Bible had been translated into Maori under the C.M.S mission leadership of Reverend Henry Williams:

‘On 30 December 1837, Colenso entered in his ‘Day and Waste Book’: ‘Finished printing the New Testament, 5000 copies demy 8vo., Glory be to God alone!’ (Quoted in A.G. Bagnall and C.G. Petersen, William Colenso, Wellington 1948, pg. 49).

In these translation efforts, Maori advisors were consulted and the best speakers of Maori to be found amongst the missionaries collaborated in the ceaseless, intensive production of printed materials. During the treaty-drafting era, Reverend Robert Maunsell was translating the Old Testament of the Bible into the Maori language. By 1842, after mission fires had destroyed his early Bible translation manuscripts, he produced Insightful Grammar. He also, finally, succeeded in his second attempt at translating the entire Old Testament of the Bible into Maori by 1856, although portions of Genesis, Exodus, Numbers and Deuteronomy were published in 1840.

The Williams family, as a whole, were all very active participants and contributors to Reverend William Williams’ Dictionary of the New Zealand Language and a Concise Grammar, 1844. Such works were never solely the efforts of any one individual, but were the product of collating information from many diverse sources of expertise, with ongoing input by many people over a period of years.

Today it would be nigh on impossible to find English/ Maori linguists of this high calibre, who lived everyday in an environment, where conversing fluently in the Maori tongue was the norm.

During February 1840 Reverend William Colenso was engaged in printing 500 prayer books, 300 primers and 200 Kupu Ui for the Port Waikato Mission station alone. The seasoned linguists of the Paihia Mission, under Henry William’s leadership, had translated all of these items into the Maori tongue for the missionary schools. During 1840 the C.M.S. Mission press also printed 1000 pamphlets, in 7 batch-lots, for Hobson’s government, several of which were translated Maori documents, completed by the missionaries. The C.M.S. Mission charged the government £14. 12/- 7d. The bill for this bilingual printing and translation work was paid on December 22nd 1840.

‘The following items were printed by Colenso in 1840, to the order of the Lieutenant-Governor: The Treaty of Waitangi in Maori (200), Circular summonsing Natives to Waitangi (100), Proclamation of the Queen’s authority (100), Proclamation regarding land purchases (100), Impounding notices (100), Circular to Natives (100), Circular warning natives against buying army stores (500), three additional printings of the, “Proclamation asserting the Queen’s Sovereignty over new Zealand” (300) [@ 100 per batch]. The final batch had slightly amended wording. Payment for this Government commissioned work was received on December 22nd, 1840 and amounted to £14. 12s. 7d’. (See: Williams, A Bibliography of Printed Maori, 1926. See also William Colenso, by A.G. Bagnall & G.C. Petersen, 1948 pg. 97).

There were ongoing and unrelenting attempts, during the two decades before 1840, to achieve a high degree of Maori literacy (see A Missionary Library. Printed Attempts to Instruct the Maori, 1815 - 1845, Journal of the Polynesian Society, LXX (1961), 429 - 49).

Concerning ‘old Reverend Williams’, Felton Mathew found him a very personable, friendly, intelligent, shrewd and entertaining travel companion, although Felton didn’t always care much for Henry’s Sunday sermons. In 1835 Reverend Henry Williams was actively involved in translating Busby’s Declaration of Independence, in behalf of the Confederation of United Chiefs, which still exists in his handwriting

For the most part, the criticism levelled by ignorant, so-called historians, related to the translating abilities of Henry and Edward Williams is based upon the mistaken, unscholarly assumption that the Williams’, father and son duo, were working from Freeman’s "composite", but largely 3rd of February rough English draft, when they completed the Maori treaty translation. They most-certainly were not!

This otherwise, obsolete, discarded and superseded rough draft has, unfortunately, become our "official" Treaty of Waitangi, eclipsing and replacing even the Maori Tiriti O Waitangi.

However, the truth is that Henry and Edward worked from an altogether different English draft produced on the 4th of February 1840. Our historians misrepresent the translators, by stating that the following English draft text shown below ... (left column) was the Williams’ translation-source for the Maori Tiriti O Waitangi (middle column)… displayed alongside a back-translation of the Maori language text (right column) from 1869.

The only way our grievance industry-aligned historians can legitimise the existence of the politically preferred, English treaty wording is to belittle the translators by erroneous and derisive commentary. By this ploy it becomes, solely, the ability and competence of the translators that is called into question and seriously maligned, rather than any unwanted focus being drawn to, and falling upon the integrity of, the grievance industry preferred English draft that the translators are, falsely, claimed to have worked from.

Genuine scholars like Ruth Ross, in 1972, were bewildered

by claims that Busby’s 3rd of February composite draft was somehow

the source of the Maori Tiriti O Waitangi and stated, quite bluntly, that

this assertion was ‘palpably incorrect’.

Alternatively, when dispossessed farmer Allan Titford showed Nga-Puhi elder

and historian, Graham Rankin, the Littlewood Treaty document in the year

2000, Mr. Rankin immediately commented that it’s wording was exactly

the same as the Maori version.

In light of Beryl Needham and her brother, John Littlewood finding Busby’s final English draft of the Treaty of Waitangi in 1989, the long-standing puzzle concerning the vast differences in the English and Maori texts is a puzzle no more.

It is glaringly apparent that the government is using the wrong English version of the treaty in all of its legislation. There is no reason to persist with this insane policy of elevating James Stuart Freeman’s composite, largely 3rd of February, rough draft, “Royal Style” version to “official” Treaty of Waitangi status. This ad-hoc English version is not our Treaty of Waitangi and never has been. There is only one Treaty of Waitangi and it’s in the Maori language.

Let’s now compare the texts:

|

Composite "Royal Style" version assembled from early notes by James S Freeman, on 5/2/1840. Her Majesty Victoria Queen of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland regarding with Her Royal Favour the Native Chiefs and Tribes of New Zealand and anxious to protect their just Rights and Property and to secure to them the enjoyment of Peace and Good Order has deemed it necessary in consequence of the great number of Her Majesty's Subjects who have already settled in New Zealand and the rapid extension of Emigration both from Europe and Australia which is still in progress to constitute and appoint a functionary properly authorized to treat with the Aborigines of New Zealand for the recognition of Her Majesty's Sovereign authority over the whole or any part of those islands. Her Majesty therefore being desirous to establish a settled form of Civil Government with a view to avert the evil consequences which must result from the absence of the necessary Laws and Institutions alike to the native population and to Her subjects has been graciously pleased to empower and to authorize "me William Hobson a Captain" in Her Majesty's Royal Navy Consul and Lieutenant Governor of such parts of New Zealand as may be or hereafter shall be ceded to Her Majesty to invite the confederated and independent Chiefs of New Zealand to concur in the following Articles and Conditions. ARTICLE THE FIRST The Chiefs of the Confederation of the United Tribes of New Zealand and the separate and independent Chiefs who have not become members of the Confederation cede to Her Majesty the Queen of England absolutely and without reservation all the rights and powers of Sovereignty which the said Confederation or Individual Chiefs respectively exercise or possess, or may be supposed to exercise or to possess, over their respective Territories as the sole Sovereigns thereof. ARTICLE THE SECOND Her Majesty the Queen of England confirms and guarantees to the Chiefs and Tribes of New Zealand and to the respective families and individuals thereof the full exclusive and undisturbed possession of their Lands and Estates Forests Fisheries and other properties which they may collectively or individually possess so long as it is their wish and desire to retain the same in their possession; but the Chiefs of the United Tribes and the individual Chiefs yield to Her Majesty the exclusive right of Preemption over such lands as the proprietors thereof may be disposed to alienate at such prices as may be agreed upon between the respective Proprietors and persons appointed by Her Majesty to treat with them in that behalf. ARTICLE THE THIRD In consideration thereof Her Majesty the Queen of England extends to the Natives of New Zealand Her royal protection and imparts to them all the Rights and Privileges of British Subjects. [Signed] W Hobson Lieutenant Governor Now therefore We the Chiefs of the Confederation of the United Tribes of New Zealand being assembled in Congress at Victoria in Waitangi and We the Separate and Independent Chiefs of New Zealand claiming authority over the Tribes and Territories which are specified after our respective names, having been made fully to understand the Provisions of the foregoing Treaty, accept and enter into the same in the full spirit and meaning thereof in witness of which we have attached our signatures or marks at the places and the dates respectively specified Done at Waitangi this Sixth day of February in the year of Our Lord one thousand eight hundred and forty. |

The original Maori text translated by Reverend Henry Williams and Edward Williams 4-5/2/1840. Ko Wikitoria te Kuini o Ingarani i tana mahara atawai ki nga Rangatira me nga Hapu o Nu Tirani i tana hiahia hoki kia tohungia ki a ratou o ratou rangatiratanga me to ratou wenua, a kia mau tonu hoki te Rongo ki a ratou me te Atanoho hoki kua wakaaro ia he mea tika kia tukua mai tetahi Rangatira-hei kai wakarite ki nga Tangata Maori; o Nu Tirani-kia wakaaetia e nga Rangatira Maori; te Kawanatanga o te Kuini ki nga wahikatoa o te Wenua nei me nga Motu-na te mea hoki he tokomaha ke nga tangata o tona Iwi Kua noho ki tenei wenua, a e haere mai nei. Na ko te Kuini e hiahia ana kia wakaritea te Kawanatanga kia kaua ai nga kino e puta mai ki te tangata Maori ki te Pakeha e noho ture kore ana. Na, kua pai te Kuini kia tukua a hau a Wiremu Hopihona he Kapitana i te Roiara Nawi hei Kawana mo nga wahi katoa o Nu Tirani e tukua aianei, amoa atu ki te Kuini, e mea atu ana ia ki nga Rangatira o te wakaminenga o nga hapu o Nu Tirani me era Rangatira atu enei ture ka korerotia nei. KO TE TUATAHI Ko nga Rangatira o te wakaminenga me nga Rangatira katoa hoki ki hai i uru ki taua wakaminenga ka tuku rawa atu ki te Kuini o Ingarani ake tonu atu-te Kawanatanga katoa o ratou wenua. KO TE TUARUA Ko te Kuini o Ingarani ka wakarite ka wakaae ki nga Rangatira ki nga hapu-ki nga tangata katoa o Nu Tirani te tino rangatiratanga o ratou wenua o ratou kainga me o ratou taonga katoa. Otiia ko nga Rangatira o te wakaminenga me nga Rangatira katoa atu ka tuku ki te Kuini te hokonga o era wahi wenua e pai ai te tangata nona te Wenua-ki te ritenga o te utu e wakaritea ai e ratou ko te kai hoko e meatia nei e te Kuini hei kai hoko mona. KO TE TUATORU Hei wakaritenga mai hoki tenei mo te wakaaetanga ki te Kawanatanga o te Kuini-Ka tiakina e te Kuini o Ingarani nga tangata Maori; katoa o Nu Tirani ka tukua ki a ratou nga tikanga katoa rite tahi ki ana mea ki nga tangata o Ingarani. [signed] William Hobson Consul & Lieutenant Governor Na ko matou ko nga Rangatira o te Wakaminenga o nga hapu o Nu Tirani ka huihui nei ki Waitangi ko matou hoki ko nga Rangatira o Nu Tirani ka kite nei i te ritenga o enei kupu, ka tangohia ka wakaaetia katoatia e matou, koia ka tohungia ai o matou ingoa o matou tohu. Ka meatia tenei ki Waitangi i te ono o nga ra o Pepueri i te tau kotahi mano, e waru rau e wa te kau o to tatou Ariki. |

Translation from the Original Maori by, Mr. T.E. Young, Native Department (1869) Victoria, Queen of England, in her kind thoughtfulness to the Chiefs and Hapus of New Zealand, and her desire to preserve to them their chieftainship and their land, and that peace may always be kept with them and quietness, she has thought it a right thing that a Chief should be sent here as a negotiator with the Maoris of New Zealand - that the Maoris of New Zealand may consent to the Government of the Queen of all parts of this land and the islands, because there are many people of her tribe that have settled on this land and are coming hither. Now the Queen is desirous to establish the Government, that evil may not come to the Maoris and the Europeans who are living without law. Now the Queen has been pleased to send me, William Hobson, a Captain in the Royal Navy, to be Governor to all the places of New Zealand which may be given up now or hereafter to the Queen; an he give forth to the Chiefs of the Assembly of the Hapus of New Zealand and other Chiefs the laws spoken here. The First The Chiefs of the Assembly, and all Chiefs also who have not joined the Assembly, give up entirely to the Queen of England for ever all the Government of their lands. The Second The Queen of England arranges and agrees to give to the Chiefs, the Hapus and all the people of New Zealand, the full chieftainship of their lands, their settlements and their property. But the Chiefs of the Assembly, and all the other Chiefs, gives to the Queen the purchase of those pieces of land which the proprietors may wish, for such payment as may be agreed upon by them and the purchaser who is appointed by the Queen to be her purchaser. The Third This is an arrangement for the consent to the Government of the Queen. The Queen of England will protect all the Maoris of New Zealand. All the rights will be given to them the same as her doings to the people of England. William Hobson Now, we the Chiefs of the Assembly of the Hapus of New Zealand, now assembled at Waitangi. We also, the Chiefs of New Zealand, see the meaning of these words: they are taken and consented to altogether by us. Therefore are affixed our names and marks. This done at Waitangi, on the sixth day of February, in the year one thousand eight hundred and forty, of Our Lord. |

It can be readily seen that the English text shown (left), which is assumed to be the source or mother document of Reverend Williams’ Maori translation, is far heavier and wordier than its Maori version counterpart. The sentence order differs quite considerably, as does the word weight per sentence. Maori people had visited or were living in Britain and Australia by 1840 and Maori-equivalent words for Kingdom, Favour, Emigration, Europe, Functionary, Pre-emption, Ireland, Australia, Forests and Fisheries either existed or could be very closely approximated. These words are not found in the Maori Tiriti O Waitangi text because they were not in Busby’s final English draft, handed to the translators at 4 p.m. on the 4th of February 1840.

The question goes begging: Why would adept and seasoned translators of the Maori language come up with a text that was so radically different to what the legislators wished be said?

Reverend Henry Williams had been a stalwart and hard working missionary in New Zealand for 17-years when he undertook to complete this treaty translation. As Head of the C.M.S. Mission, he was a very fluent speaker of Maori. His son Edward was 21-years old and had been raised amongst the Nga-Puhi tribe. He had a reputation of being a scholar “par excellence” in the Nga-Puhi dialect.

In all respects, Edward was a very talented and serious young man, with a wonderful command of language and also an adept artist. He later accompanied Major Thomas Bunbury on a treaty-signing mission to the South Island and Stewart Island, acting as interpreter. Of that journey he wrote a fully detailed report for the historical record and produced a beautifully executed drawing of H.M.S Herald lying at anchor in Sylvan Cove, Stewart Island.

Edward Marsh Williams’ beautifully executed drawing of H.M.S Herald lying at anchor in Sylvan Cove, Stewart Island in 1840. Edward had been raised amidst Maori and was considered to be a scholar “par-excellence” in the Nga-Puhi dialect.

It is a contradiction that historians, who are highly critical of the Williams’ Maori translation as it compares to the official English version, will also admit, in the same breath, that the final English draft, from which the Williams’ team worked, ‘went missing’. To find the text wording in English that the translators worked from, it might have been more logical to search for a February 1840 English draft that mirrored a Maori back-translation perfectly.

In actual fact, the correctly worded English text (as found in the Clendon & Wilkes despatches) has been available on microfilm in our New Zealand archives and libraries since 1953.

The correct wording has existed in United States Government records since February 20th 1840, alongside two other duplicate originals, from April 3rd & April 5th 1840.

In truth, the Williams’ father and son team did a perfect job of translating the true or actual final draft that they were handed on the 4th of February 1840 at 4 pm and required to work from.

Researchers are encouraged to return to the 16-pages of rough notes that preceded the final draft to see where Freeman grabbed bits and pieces or more substantial lumps in order to create several, variable, ad-hoc, "composite", ‘Royal-Style’ versions, one of which has graduated into becoming our "official" treaty. It will be seen that he had to take it upon himself to add some linking text to tie things together or was required to edit out large sections of superfluous nonsense.

Clearly, there is no final draft, sufficient for translators to work confidently from, to be found amidst the 16-pages of rough notes. There absolutely had to be a final draft beyond these 16-pages of raw and disjointed concepts.

It’s bizarre that our lack-lustre historians can accept that Hobson travelled halfway around the world to secure rights for the European settlers (Ngati-Wikitoria), but then forgot to mention those rights in the final English treaty draft. The fact of the matter is that settler rights, equal to Maori, were fully included!

|

The Littlewood Treaty, which was Busby’s final draft of the 4th of February 1840 Her Majesty Victoria, Queen of England in Her gracious consideration of the chiefs and the people of New Zealand, and Her desire to preserve to them their lands and to maintain peace and order amongst them, has been pleased to appoint an officer to treat with them for the cession of the Sovreignty of their country and of the islands adjacent, to the Queen. Seeing that many of Her Majesty’s subjects have already settled in the country and are constantly arriving, and it is desirable for their protection as well as the protection of the natives, to establish a government amongst them. Her Majesty has accordingly been pleased to appoint me William Hobson, a captain in the Royal Navy to be Governor of such parts of New Zealand as may now or hereafter be ceded to Her Majesty and proposes to the chiefs of the Confederation of United Tribes of New Zealand and the other chiefs to agree to the following articles.

The chiefs of the Confederation of the United Tribes and the other chiefs who have not joined the confederation, cede to the Queen of England for ever the entire Sovreignty of their country. Article Second The Queen of England confirms and guarantees to the chiefs and the tribes and to all the people of New Zealand, the possession of their lands, dwellings and all their property. But the chiefs of the Confederation of United Tribes and the other chiefs grant to the Queen, the exclusive rights of purchasing such lands as the proprietors thereof may be disposed to sell at such prices as may be agreed upon between them and the person appointed by the Queen to purchase from them. Article Third In return for the cession of the Sovreignty to the Queen, the people of New Zealand shall be protected by the Queen of England and the rights and privileges of British subjects will be granted to them.

Now we the chiefs of the Confederation of United Tribes of New Zealand assembled at Waitangi, and we the other tribes of New Zealand, having understood the meaning of these articles, accept of them and agree to them all.In witness whereof our names or marks are affixed. Done at Waitangi on the 4th of Feb. 1840. |

The Maori text translated by Reverend Henry Williams & Edward M. Williams 4-5/2/1840 Ko Wikitoria te Kuini o Ingarani i tana mahara atawai ki nga Rangatira me nga Hapu o Nu Tirani i tana hiahia hoki kia tohungia ki a ratou o ratou rangatiratanga me to ratou wenua, a kia mau tonu hoki te Rongo ki a ratou me te Atanoho hoki kua wakaaro ia he mea tika kia tukua mai tetahi Rangatira-hei kai wakarite ki nga Tangata Maori; o Nu Tirani-kia wakaaetia e nga Rangatira Maori; te Kawanatanga o te Kuini ki nga wahikatoa o te Wenua nei me nga Motu-na te mea hoki he tokomaha ke nga tangata o tona Iwi Kua noho ki tenei wenua, a e haere mai nei. Na ko te Kuini e hiahia ana kia wakaritea te Kawanatanga kia kaua ai nga kino e puta mai ki te tangata Maori ki te Pakeha e noho ture kore ana.Na, kua pai te Kuini kia tukua a hau a Wiremu Hopihona he Kapitana i te Roiara Nawi hei Kawana mo nga wahi katoa o Nu Tirani e tukua aianei, amoa atu ki te Kuini, e mea atu ana ia ki nga Rangatira o te wakaminenga o nga hapu o Nu Tirani me era Rangatira atu enei ture ka korerotia nei. Ko Te Tuatahi Ko nga Rangatira o te wakaminenga me nga Rangatira katoa hoki ki hai i uru ki taua wakaminenga ka tuku rawa atu ki te Kuini o Ingarani ake tonu atu-te Kawanatanga katoa o ratou wenua. Ko Te Tuarua Ko te Kuini o Ingarani ka wakarite ka wakaae ki nga Rangatira ki nga hapu-ki nga tangata katoa o Nu Tirani te tino rangatiratanga o ratou wenua o ratou kainga me o ratou taonga katoa. Otiia ko nga Rangatira o te wakaminenga me nga Rangatira katoa atu ka tuku ki te Kuini te hokonga o era wahi wenua e pai ai te tangata nona te Wenua-ki te ritenga o te utu e wakaritea ai e ratou ko te kai hoko e meatia nei e te Kuini hei kai hoko mona.

Hei wakaritenga mai hoki tenei mo te wakaaetanga ki te Kawanatanga o te Kuini-Ka tiakina e te Kuini o Ingarani nga tangata Maori; katoa o Nu Tirani ka tukua ki a ratou nga tikanga katoa rite tahi ki ana mea ki nga tangata o Ingarani. [signed] William Hobson Consul & Lieutenant Governor Na ko matou ko nga Rangatira o te Wakaminenga o nga hapu o Nu

Tirani ka huihui nei ki Waitangi ko matou hoki ko nga Rangatira

o Nu Tirani ka kite nei i te ritenga o enei kupu, ka tangohia ka

wakaaetia katoatia e matou, koia ka tohungia ai o matou ingoa o

matou tohu. |

Translation from the Original Maori by, Mr. T.E. Young, Native Department (1869) Victoria, Queen of England, in her kind thoughtfulness to the

Chiefs and Hapus of New Zealand, and her desire to preserve to them

their chieftainship and their land, and that peace may always be

kept with them and quietness, she has thought it a right thing that

a Chief should be sent here as a negotiator with the Maoris of New

Zealand - that the Maoris of New Zealand may consent to the Government

of the Queen of all parts of this land and the islands, because

there are many people of her tribe that have settled on this land

and are coming hither. Now the Queen has been pleased to send me, William Hobson, a Captain in the Royal Navy, to be Governor to all the places of New Zealand which may be given up now or hereafter to the Queen; an he give forth to the Chiefs of the Assembly of the Hapus of New Zealand and other Chiefs the laws spoken here. The First The Chiefs of the Assembly, and all Chiefs also who have not joined the Assembly, give up entirely to the Queen of England for ever all the Government of their lands. The Second The Queen of England arranges and agrees to give to the Chiefs, the Hapus and all the people of New Zealand, the full chieftainship of their lands, their settlements and their property. But the Chiefs of the Assembly, and all the other Chiefs, gives to the Queen the purchase of those pieces of land which the proprietors may wish, for such payment as may be agreed upon by them and the purchaser who is appointed by the Queen to be her purchaser. The Third This is an arrangement for the consent to the Government of the Queen. The Queen of England will protect all the Maoris of New Zealand. All the rights will be given to them the same as her doings to the people of England. William Hobson Now, we the Chiefs of the Assembly of the Hapus of New Zealand, now assembled at Waitangi. We also, the Chiefs of New Zealand, see the meaning of these words: they are taken and consented to altogether by us. Therefore are affixed our names and marks. This done at Waitangi, on the sixth day of February, in the year one thousand eight hundred and forty, of Our Lord. |

In light of Beryl Needham and her brother, John Littlewood finding Busby's final English draft of the Treaty of Waitangi in 1989, the longstanding puzzle concerning the vast differences in the English and Maori texts is a puzzle no more. It is apparent that the government is knowingly using the wrong English version of the treaty in all of its legislation. There is no reason to persist with this insane policy of using the "composite", largely 3rd of February rough draft as our official English and, by consequence, the legislative text for any-and-all Treaty of Waitangi legal interpretations.